Aunt Janel: a beautiful woman who, for me, only exists in stories from family members, old photos, and in one short but very vivid memory of a hospital bed in my Grandparent's living room. I’ve heard the joke more than once that a ‘Part II’ could be ‘18 Aunts,’ and I do have eighteen amazing aunties who are the backbone behind my eighteen legendary uncles. And I’ve often wondered how to honor them in the work.

But I’m writing about Aunt Janel because she is no longer with us.

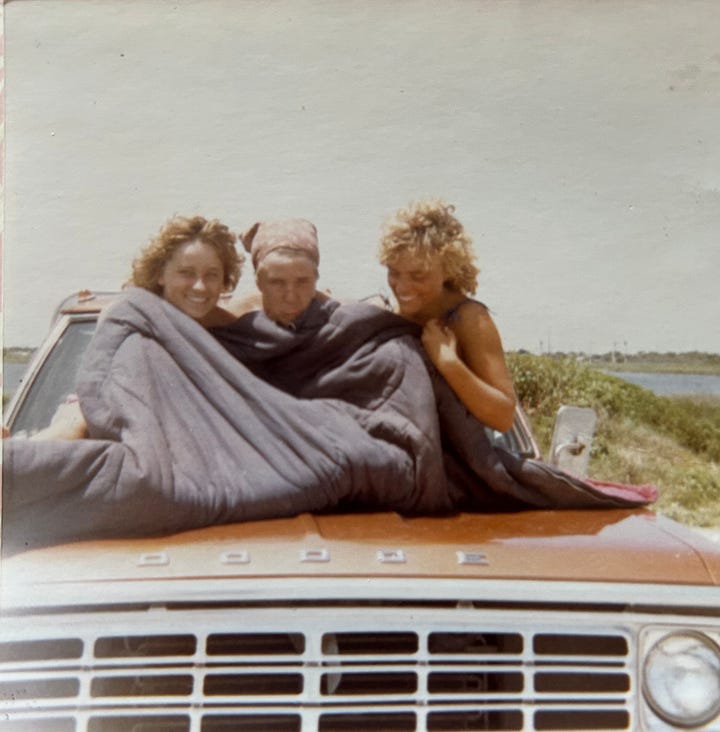

My father’s big sister is a tragic story of a shy Apostolic, who all the boys had crushes on, loved music and adventure, and drove down to Texas with friends and biked back, who journaled along the way and included a story of calling home and my Dad answering, who met a man, got married, and had two kids, who dyed her hair, wore makeup, and enjoyed concerts more than anything, who, like a gorgeous melody, graced the earth with beauty but faded far too soon, now existing in recorded memories and the way she made people feel… I often wonder how the Peterson siblings managed it all, tragically losing a brother and a sister in their thirties.

Janel: my nineteenth aunt. And I have a nineteenth uncle who I have no memory of meeting—although they both would’ve been around when I was a toddler. Aunt Janel left two children—my first cousins—who I have no memories of either.

But the best thing about coming home has been reconnecting with everyone, including Cousin Cassandra, who looks so much like her mother Aunt Colleen was brought to tears by the sight of her when they reconnected after too many years apart.

Cassandra, like me, has been writing. And I love how we now call each other “Cousin,” like in the show, The Bear, and how it reaffirms our relationship because we spent over thirty years without calling each other anything.

We’ve been chatting a lot about our parallel creative journeys, trying to craft something for our long-deceased parents, to capture their essence in words, intimately preserve their legacies, and share their stories while also learning what it means to lose someone in childhood and live most of our lives staring in longing at the space they left, at the crater caused by tragedy, and how to heal a wound so eternally deep.

I never knew Aunt Janel, and Cassandra is a writer. So I thought it’d be best to tell her mother’s story in her voice.

What follows are the words of My Cousin…

When Mitchell asked me to contribute some memories of my Mom Janel to his blog, I got a bit teary-eyed. Since losing her in 1993, one of the saddest parts of her absence has been not being able to introduce her to my friends and loved ones.

Now, thanks to this blog, more people will know about my beautiful mother.

What I remember most about Mom was her quiet strength. As a true Finn, she wasn’t known to speak about her feelings, but you could see how she felt by looking at her face.

I learned to read people from Mom.

She always talked to me like an adult, she loathed “baby talk.”

She wasn’t super affectionate with me, but she did let me sleep with her from time to time or came into bed with me when I was scared about the wicked witch in Snow White. She cuddled Shane (named after the Western film), my little brother, a bit more. Something I always felt a bit jealous of. She didn’t want Shane and I to be watching TV after school, so she would send us outside and tell us to come home when it started getting dark.

Growing up I always remember music playing.

She liked Heart, and I remember her and Shane laughing at me because I thought their song “Barracuda” was about a monkey. Mom fashioned her hair to look like Joan Jett. She became the ultimate 80s hair band babe. I have vivid memories of her getting all dolled up to go to a concert. With my dad she went to see bands like Iron Maiden, Ozzy Osbourne, and Metallica, just to name a few.

She was super active and loved to take us on long walks, picking dandelions on the way. We’d make wishes on the fluffy white ball seed heads by blowing them into the air or she’d pop the yellow flower off the stem and say, “Mama had a baby and her head popped off.”

She taught us how to flip around on the monkey bars, and I remember her doing stretches and splits in the living room.

Mom loved animals, I have old notebooks of hers with cut-out photos of monkeys, kittens, and her favorite kind of dog, Collies.

She was an excellent baker. I vividly remember cinnamon rolls rising, pasty making, and her famous Christmas sugar cookies.

Although she was way too frugal to ever take us to the theater, she loved movies. The ones that remind me of her the most are Pillow Talk starring Doris Day and Rock Hudson, North by Northwest with Cary Grant, The Untouchables with Kevin Cosner and Sean Connery, and we’d watch the old Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis classics. She was a bit cautious of the newer films with their vulgarity. She was known to leave the room or take back the rented VCR if there was any kind of nudity on screen.

Mom could be silly too.

She loved McDonald’s and their Fish O’ Fish but would never let us eat at Wendy’s. She said, “burgers aren’t supposed to be square.” When I asked about White Castle burgers she said, “That’s different.”

She wouldn’t let me have candy when I asked for it, so I started stealing it, and she wasn’t happy with me at all—I even got banned from a grocery store in Escanaba. She came and got me, put my peach bike in the back of our rusted pickup, and promised not to tell my dad. I was confused because, even though I knew stealing was wrong, she had stolen a set of McDonald's miniature Barbies a month prior because the people at the garage sale (her favorite thing) were charging too much.

In June 1992, my family moved from Escanaba, Michigan to Glascow, Kentucky. We were so excited to be out of trailer life and into a house with a huge yard and a forest to explore.

One day, we went to the grocery store and Mom started to act strange… and then told me she couldn’t see anything.

I had to be her eyes and direct her to the nearest hospital a little over a mile from the IGA.

Mom had been sick in Escanaba with night sweats, constant headaches, and a rash on her legs. I had gone to doctor’s appointments with her where they couldn’t figure out what was wrong. She only told me once that she couldn’t understand why she couldn’t get better… but the blindness was a whole new level of scary.

I had to leave her right after that to visit my dad’s sister in Rome, NY.

A few months later, I was in Bowling Green, Kentucky being told by my father that Mom was going to die “in two weeks.”

I asked what it was and was told encephalitis. I thought her death diagnosis was a mistake because I had a teacher in the fifth grade who had encephalitis and got over it. I thought the doctors were wrong again and there was a chance she would get better.

I didn’t see her much after that.

I’ve been told she didn’t want me to see her getting sicker, but my Aunt Lynn recently told me she was always asking for us.

I saw her three more times before she died on October 23, 1993, my parent’s 11th wedding anniversary.

Each time was more frightening than the last.

The last time I saw her was in a room at Calumet Public Hospital (now known as Aspirus Keweenaw) in Calumet, Michigan, where we had to wear a medical robe, hairnet, mask, gloves, and booties on our shoes. I didn’t understand at the time why she was in her own wing of the hospital by herself and why I couldn’t touch her skin.

The last thing she ever said to me was, “I never told him,” about my last candy-stealing incident.

She was 31 years old.

It wasn’t until nine years later that I would learn the truth about Mom’s death.

My dad showed me her death certificate one day and the cause of death popped out of the page and slapped me in the face, “AIDS.” He told me, “It wasn’t because of sex or drugs” and that it was likely from a blood transfusion. We will never know exactly how it happened but I have my theories.

The stigma and shame surrounding HIV/AIDS forced my family to lie to me for almost a decade and keep me from her side of the family. I felt completely disconnected from her for so long. She was rarely mentioned and photos of her were tucked away.

It hurt too much to look at them.

At first, as a ten-year-old, I would beg her to come to me as an angel, and I would cry while speaking to her, processing her death an impossible task.

It wasn’t until I outlived Mom when I was 32 and quit drinking that I was able to begin grieving.

I decided around that time that I needed to tell her story and speak out about how AIDS in women was completely ignored. I want to not only let people know who she was but also avenge her death through a memoir.

Since I began that process, I’ve reconnected with her side of the family, visited her grave, and discovered a new spiritual relationship with her. I talk to her and ask her questions, she replies in my mind’s eye or through songs and images on TV.

Feeling this connection with her keeps me sane.

I can’t bear the idea that she is just gone. Instead, I like to believe she’s guiding me, and I’m never really alone.

I’ve done a lot of soul searching, research, and studying of what happens to us when we die, and I believe her soul has been with me this whole time.

This doesn’t mean I don’t wish she was here every single day. My longing for her used to be destructive, but today I try my best to honor her memory with my own life.

I feel like I’m living for the both of us now.

I want her to be remembered for how she lived, not the tragic way she died.

My hope is that with writings like these my strong beautiful mother, Janel, will be remembered eternally.

Follow Cassandra’s journey here:

Thank you for reading.

And thank you, Cousin, for the beautiful contribution.

This is gorgeous and a beautiful memorial. I’ve never lived during a time where there wasn’t medicine for HIV. I can’t imagine the fear and stigma back then.

Tears flowed reading this piece, remembering that time. I am certain she feels the love. Beautiful work you two.