Growing up in Upper Michigan, the winters were unbearably long. Thanks to the Great Lakes, they’re longer than in much of Canada. They’re trick-or-treating with snow pants under your costume and Memorial Day Parades with melting, sand-covered snowbanks on the street — long.

A winter that takes up most of the year makes for heartbreakingly brief summers, and that, in turn, means a short wedding season. Throw in a tight-knit church and an extremely large family, and it’s a jam-packed wedding season.

For younger me, it seemed like we were always at weddings.

Many of our summer Saturdays were spent back in church with the whole extended clan, listening to sermons being read and vows repeated as I drew on a tiny sketch pad or completely zoned out and imagined my army men rappelling around the dangling light fixtures Toy Story style.

Weddings in the church typically followed the same script with hundreds of family and friends from the congregation, ham sandwiches on rolls, cheesy potatoes, and lots of raspberry jello eaten on fold-out tables in the dining area. Given the cultural conventions of the church, there was no DJ, no dancing, and definitely no alcohol.

The jello was the wedding highlight for most of the kids, but by the time I was ten, what appealed to me were the fathers and grandfathers outside smoking cigars.

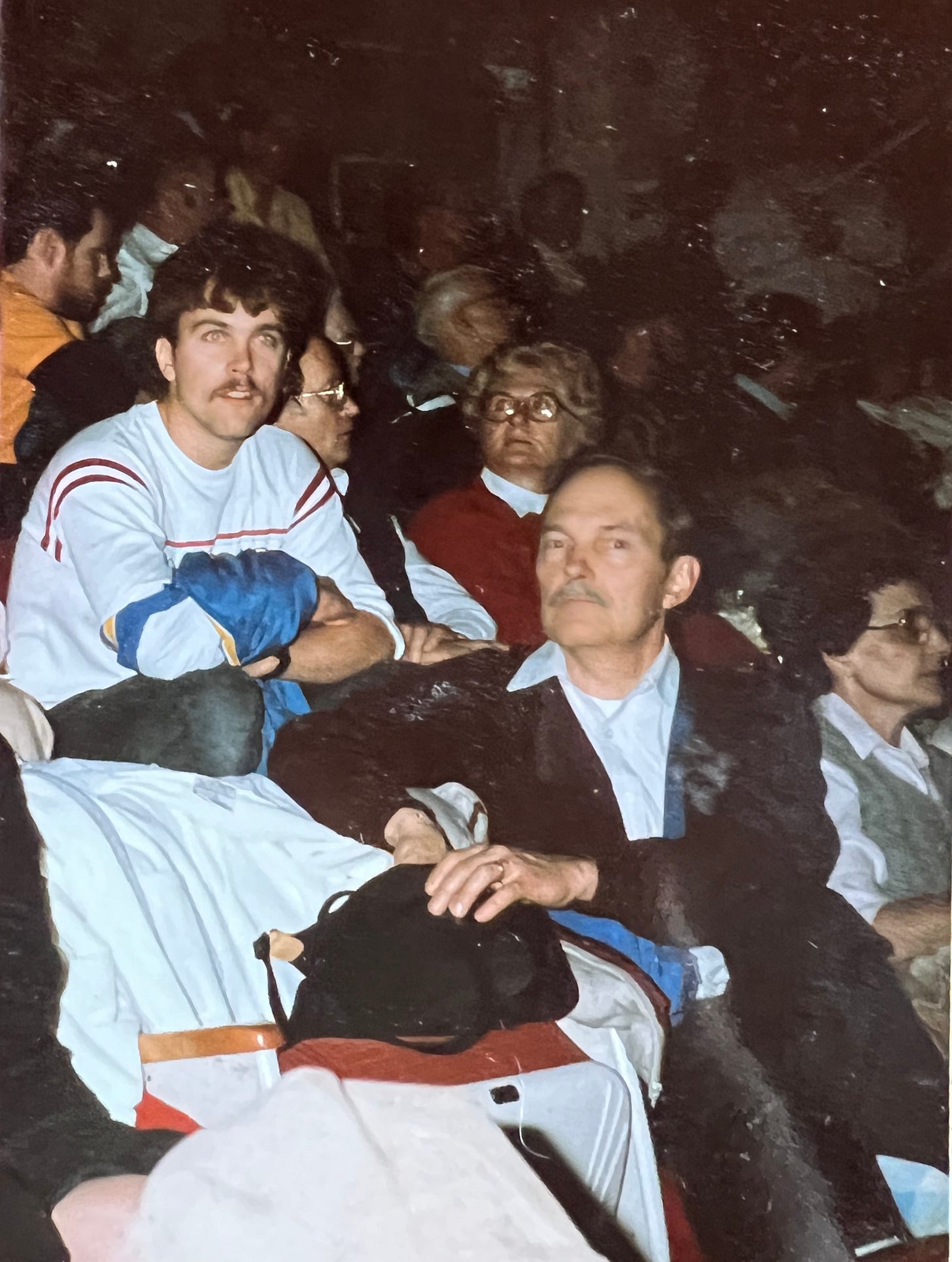

My maternal grandfather chain-smoked cigarettes and worked a ton, so he wasn’t around all that much. He was an old-school dude and always a bit of a mystery to me, but we spent a ton of time at their house, watching TV, playing Sega, and running around their lakefront property.

As kids growing up with a garden and organic food, going to my grandparents’ house was like entering the devil’s playground. There were ashtrays on all the tables, that comforting, smokey scent, and there was a plethora of forbidden, foreign luxury items like name-brand cereal, Spaghetti-O’s from the commercials, and those unbelievably good Little Debbie Snacks.

Our house was healthy. It was organic whole-grain everything and soy milk. My mother made nutritious meals from different parts of the world. We begged for Pop-Tarts and pizza rolls and got couscous and carrot soup. Other kids who brought lunch to school ate peanut butter and jellies on Wonderbread and had toxically bright fruit roll-ups while we stared in envy, holding our crumbling whole-wheat sandwiches and organic brown fruit leathers.

Our house was like a health food store, so our grandparents’ was a smokey, processed-sugar den of sin.

To this day, the smell of cigarettes doesn’t bother me at all and is actually comforting.

When I was ten, we went to another spring wedding in church. It was the same as the one before it with a religious ceremony, raspberry jello, and the men outside smoking cigars and cracking jokes.

At some point in the following days, a cigar showed up in our food pantry, the closet-sized pantry our family of eight had that was filled with organic food.

There on one of the shelves was a cigar wrapped in plastic.

I couldn’t believe it. I picked it up and smelled it but, with the plastic, couldn’t get a scent. I smelled harder, trying to get that delicious, smokiness from the weddings or from my grandparents’ house but there was nothing.

“How is there a cigar in our food pantry?” I thought. “Who put it here and why?”

The next day, I opened the pantry door, and there was that cigar.

It was there again the next day and then the next.

“Nobody is going to smoke that thing,” I thought.

After not having seen it move for many days, one morning I took the cigar and hid it on the first shelf behind bags of pasta and flour.

Then I waited.

I went about my day, waiting for my father or mother to shout, “Where did the cigar from that wedding go?” I was prepared to say, nonchalantly, “Hmm, maybe it fell behind these things on the other shelf,” but nothing happened. The whole day passed and nobody noticed it was missing.

The next day passed and it was the same, crickets.

After a few days, I knew nobody cared enough and that wedding cigar was up for grabs.

Living super rural, having a horse farm across from our house, and a small handful of neighbors within a half-mile radius, we had a garden, a seven-acre yard, and miles of forest to explore. We also burned our paper trash.

One of our chores was to go to a barrel and burn old newspapers, letters, and organic cereal boxes.

So, on the fourth or fifth day the cigar went unnoticed, I took it from behind the pasta, grabbed the paper bags and boxes, and snuck out to the burn barrel.

I lit the brown paper grocery bags filled with random burnables and watched them gather flames. Then, I stepped behind the corner of our large sheet-metal pole barn.

I unwrapped the cigar and smelled it like I had seen the guys do at weddings. It smelled like raisins, not the soothing vanilla smokiness I remembered.

I took the lighter out of my pocket, put the cigar to my lips, sparked it, and held the flame to the end. I remembered when men first started smoking, they would take short puffs as the cigar got going, and they blew the smoke, puffing and blowing, puffing and blowing until the end was a glowing circle ember.

I was puffing but nothing happened. I kept the flame on the end and tried to inhale but nothing happened. I very clearly remember voicing the words, “this cigar sucks,” as my paternal grandfather, an eternally-kind non-smoker, emerged from around the corner.

“Hey, Mitch.”

I froze.

“Is that a cigar?!” He asked in disbelief, pointing as a fat, brown stogie was smoldering between my ten-year-old fingers.

I wrangled in suffering, not even thinking. I was cornered. Time slowed as I could feel my cheeks flush and hear my heart thumping in my ears.

I didn’t say a word.

Then, quickly, I threw the cigar into the melting snowbank and ran full speed right passed him.

I ran as fast as I could into the house, up the stairs, into my room, closed the door, and waited for the hammer to drop.

I was screwed.

He had just witnessed me, his ten-year-old grandson, attempting to smoke. His next logical steps were to tell my father, and then my mother, and then I would be dragged downstairs by my ear to my sentencing and probably be grounded until I was eighteen.

I sat on my bed, panicking and contemplating the punishment, trying to gauge how badly I had messed up. Would it be extra chores? Military boarding school?! Death?!

But after an hour passed and then two, I began to get confused. “If he told my parents, they’d be here already,” I thought as I sat and waited.

I don’t clearly remember what happened next but I know my grandfather was gone by the time I emerged from my room hours later.

I never heard about it from my mother or father, and I remember, days later, going back out to the burn barrel, finding the cigar, and trying to smoke the soggy thing again, not knowing I needed to cut off the tip.

I’m pretty sure my grandfather never told anyone. And now, being an adult, I look at it from his perspective, imagine catching a ten-year-old smoking a cigar, and can’t believe I didn’t get into trouble.

My father passed away the next summer, so it’s possible my grandfather told him and he somehow didn’t do anything. When I brought this incident up with my mother, twenty years later, she had no recollection of ever being told that her elementary-school-aged son was caught toking on a stogie.

My grandpa also passed before I ever asked him about this story. So, I’m not sure if he told my father, and then my father was too busy, or he simply said f*ck it.

I’ll never know for sure.

But I like to think my grandpa ain’t no snitch.

The horror of being a kid that doesn’t have the cool food at lunch time 🫣😂 mmmm those Debbie cakes and freezer full of Schwann’s ice cream bars, universal peterson desire to get hopped up on sugar at G + G’s house

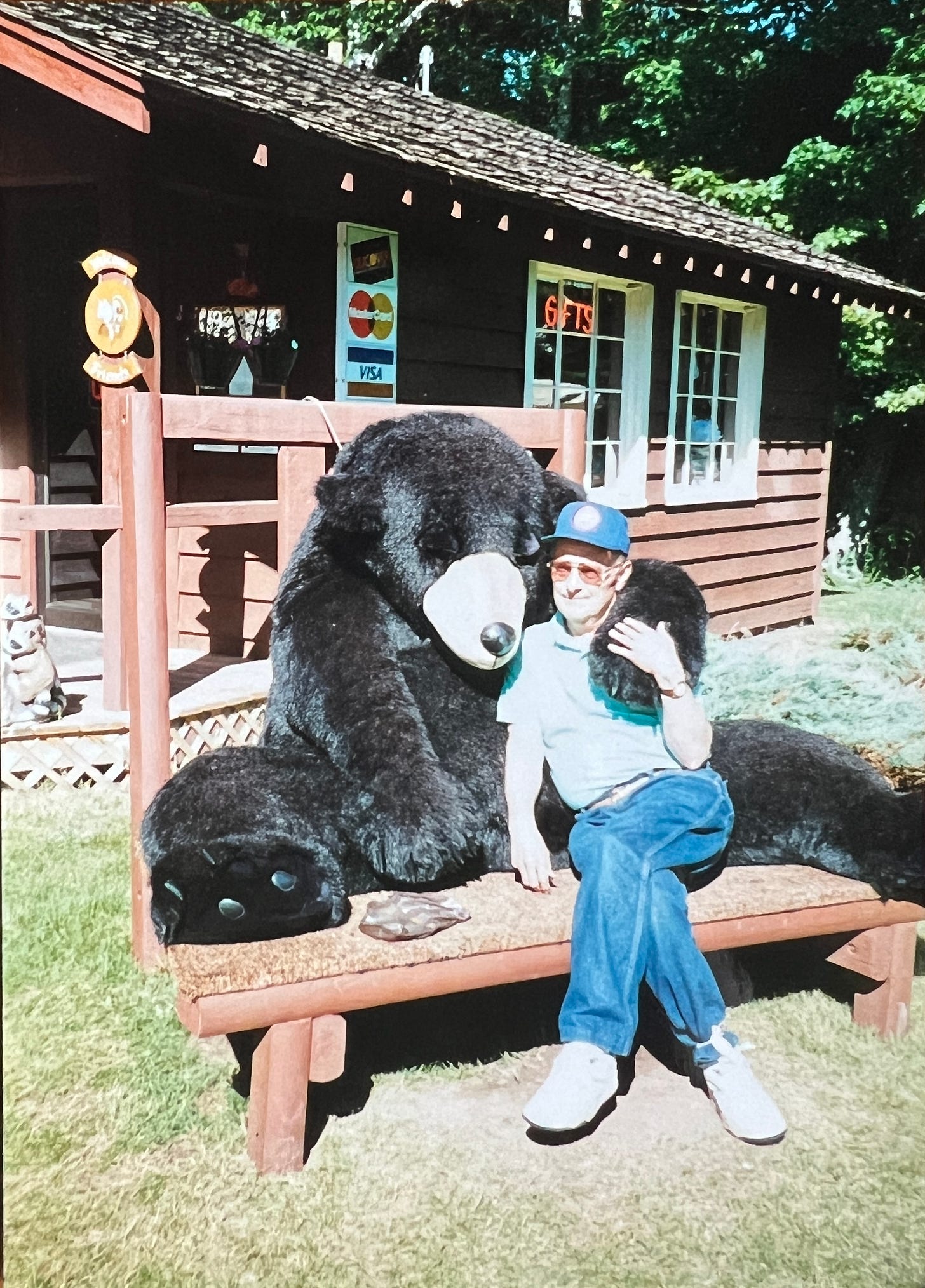

Great story! Sounds like grandpa! He was so kind, and never lost his temper! At least I never saw it! 🩵